By Lisa Huiqin Wang – Link to article

The Eli and Edythe Broad Center of Regenerative Medicine and Stem Cell Research at UCLA (pictured above) is located at the south end of campus. In November 2021, researchers at the center published a study detailing a new, more convenient way to generate cells that help fight cancer.

UCLA researchers have developed a way to genetically engineer cells to create a potentially more cost-effective treatment for cancer.

In the Nov. 16 study, researchers created a method of growing cancer-fighting cells to refine immunotherapy – an alternative to chemotherapy that helps mobilize the patient’s immune system to kill cancer cells, according to the American Cancer Society.

Immunotherapy drugs first emerged in 1986 when the Food and Drug Administration approved a protein for the treatment of cancer. Since then, advances in drug development and ongoing research have increased the number of people who can benefit from immunotherapy. The estimated percentage of patients in the United States with cancer eligible for one type of immunotherapy increased from approximately 2% in 2011 to approximately 27% by 2015 and 44% in 2018, according to a 2019 study from Oregon Health & Science University.

Immunotherapy helps the patient’s immune system recognize and remember what the cancer cell looks like. After identifying them, the patient’s immune system destroys the cancerous cells for long-term protection for cancer, also known as immunomemory.

However, depending on the patient, standard methods of immunotherapy can be time-consuming and costly – often more than $100,000 per year. Unlike previously standard treatment methods, the new treatment overcomes issues by being able to cater to a wider patient population rather than being on an individual treatment method basis.

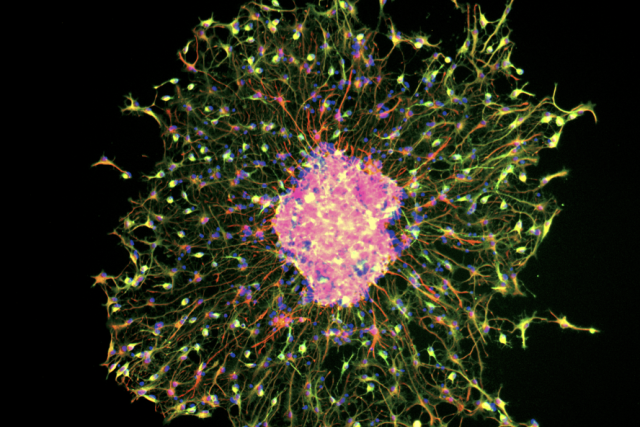

One current method works by taking T cells from the patient’s blood, teaching them how to attach to cancerous cells, and then giving them back to the patient’s body so they can kill cancer, according to the Cancer Research Institute. In order to improve the current methods of immunotherapy, the researchers worked to modify immune cells known as invariant natural killer T cells, which originate in human bone marrow and activate other immune cells to fight off cancer.

This study is special for its defining characteristic of being an “off-the-shelf” therapy, said Yanruide Li, the lead author of the study and a postdoctoral student at the UCLA Molecular Biology Institute.

“’Off-the-shelf’ means we work on the plate or dishes – we don’t work on the mice, we don’t work in the human,” Li said.

The method allowed the researchers to generate tens of millions of cancer-fighting cells from dishes of stem cells, he added.

The invariant natural killer T cells can also target a variety of cancers, including blood cancers and tumors.

According to the study, unlike other methods, the invariant natural killer T cells were significantly more effective at killing cancerous tumors such as leukemia, melanoma, lung, prostate and myeloma. Certain types of invariant natural killer T cells can fight virus strains in the future, including the COVID-19 virus, Li said. They may also help prevent complications in cancer patients who receive donated bone marrow or stem cells as part of their treatments.

Robert Prins, a tumor immunologist and a professor of neurosurgery, said the development of cells can treat tumors because these cells can stop the cancer from spreading earlier on.

“Standard surgery, chemotherapy and radiation can certainly do something, … but it doesn’t cure the disease,” Prins said. “Immunotherapy is, I think, theoretically one of the best new treatments that can target isolated tumor cells before they metastasize elsewhere. … I think (immunotherapies) are going to be the next new revolution in this cancer therapy.”

Jonathan Draper, a second-year molecular, cell and developmental biology student, said he thinks the new invariant natural killer T immunotherapy opens up a new avenue for cancer therapy. He said this technology is advantageous because of how easily the cells are transported to many different sites.

Li said the researchers are currently working to make the cells easily accessible and feasible for patient use.