By Karen Weintraub – January 10, 2022 – APNews.com (link to article)

A Maryland man has lived for three days with a pig heart beating inside his chest.

The surgery, at the University of Maryland Medical Center, marks the first time a gene-edited pig has been used as an organ donor.

Dave Bennett, 57, agreed to be the first to risk the experimental surgery, hoping it would give him a shot at making it home to his Maryland duplex and his beloved dog, Lucky.

“This is nothing short of a miracle,” his son David said Sunday, two days after his father’s life-extending surgery. “That’s what my dad needed, and that’s what I feel like he got.”

In the nine-hour surgery, doctors replaced his heart with one from a 1-year-old, 240-pound pig gene-edited and bred specifically for this purpose.

Bennett is breathing on his own without a ventilator, though he remains on an ECMO machine that does about half the work of pumping blood throughout his body. Doctors plan to slowly wean him off.

Scientists have worked for decades to figure out how to save human lives with animal organs. More than 100,000 people sit on organ transplant waitlists, suffering terrible symptoms and side effects. About 6,000 of them die every year waiting in vain for someone else’s tragedy to provide them with a kidney, heart or lung.

Pigs have similar organs to humans. If those organs could be used in transplants, the waiting would end. People who would never be considered candidates for transplants – who never make it onto those transplant lists – could look forward to family dinners, playing with their kids or grandkids and simply going back to living their lives.

The surgical team at the University of Maryland School of Medicine

That’s the promise of so-called xenotransplantation. And the field took a major leap forward with Bennett’s surgery Friday.

“This is a truly remarkable breakthrough,” said Robert Montgomery, a transplant surgeon at NYU Langone and a heart transplant patient himself. “I am thrilled by this news and the hope it gives to my family and other patients who will eventually be saved by this breakthrough.”

In September, Montgomery moved the work forward by becoming the first to transplant a pig kidney into a person, but in that case, and a subsequent surgery in December, the person had been declared brain dead. Montgomery kept the body functioning via machine for more than two days each time, showing that the human immune system would not immediately reject a kidney from a gene-edited pig.

The Maryland procedure “takes what we did in September of 2021 to the next level,” Montgomery said. “At that point, the race was on.”

Others in the field were supportive, if a bit envious.

“We’ve all been doing this for a really long time, and I’m sure it’s got to be fun to be first,” said Joseph Tector, a transplant surgeon and xenotransplantation researcher at the University of Miami.

Tector, who focuses on kidney transplants, said he’s waiting until he’s confident he can provide reliable, durable results, “so that when we do it, we can help everybody.”

Animal rights activists object to the use of pig organs. There would be more human organs available for transplant if health authorities assumed everyone was an organ donor unless they opted out, instead of the opt-in system.

Ethicists have fewer concerns.

Animal trials are essential to begin a new therapy in humans, said the Rev. Tadeusz Pacholczyk, director of education at the National Catholic Bioethics Center in Philadelphia.

Despite years of research, “there are sure to be many more twists and turns along the road of getting our immune system to play nice with implanted animal organs,” Pacholczyk said. “I suspect this is a first step on the journey from yesterday’s ‘scientifically unimaginable’ to today’s ‘barely achievable’ to tomorrow’s ‘standard of care.’”

Patient experience

Bennett, who has been relatively healthy most of his life, began having severe chest pains in October, his son said.

He went into the University of Maryland Medical Center with severe fatigue and shortness of breath. “He couldn’t climb three steps,” said David, a physical therapist who understood the seriousness of his dad’s condition.

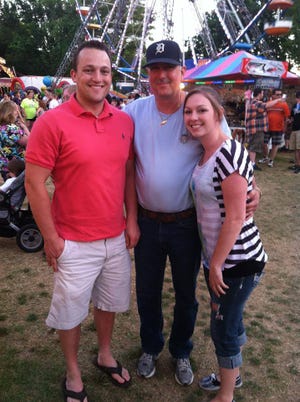

A pig heart transplant at the University of Maryland gives Dave Bennett Sr., center, more time with his family, David Bennett Jr. and Nicole (Bennett) McCray.

Two months of trying to save Bennett’s own heart didn’t work. A handful of transplant programs either formally or informally rejected him for a heart transplant. He was deemed ineligible for an artificial heart pump because of uncontrollable arrhythmia.

About 3,000 Americans a year are lucky enough to get a new heart, and 20% of those who make it to the waitlist die waiting or become too ill to receive one.

Bennett didn’t qualify for the list, because he had not followed doctors’ orders, missing medical appointments and discontinuing prescribed medications. History has shown that people with that kind of track record don’t do well with an organ transplant.

At first, Bennett didn’t want to participate in the experimental surgery. He had worked odd jobs his whole life – pool repairs, car maintenance, painting – depending on his physical strength, but two months in the hospital had made any kind of surgery risky. He didn’t want to die on an operating table.

Bennett had a change of heart, his son said, when he realized he would probably never be able to leave the hospital otherwise.

“He knew that this was his best option,” David said. “He’s a fighter and has a desire to live.”

Although Bennett has a long way to go, David said he’s optimistic about his father’s future.

The family in 2019: From left, David Bennett Jr., Preston Bennett, Dave Bennett Sr., Gillian Bennett, Nicole (Bennett) McCray, Sawyer Bennett and Kristi Bennett.

“My dad has told both of his sisters and myself, ‘Don’t worry. God is holding my hand,’” David said, describing his father as a man of faith, though not tied to any particular religion. “I believe there’s continued reason to be hopeful.”

Even if it doesn’t change his outcome, the surgery allows Bennett to leave a legacy, David said.

“Regardless of what happens, I want to help other people,” Bennett told his son before the surgery.

Bennett had a pig valve implanted almost a decade ago, and bacon is his favorite food, so the idea of receiving a part from a pig didn’t bother him much, David said, although he still hopes he’ll be able to get a human heart.

Perhaps after six months of showing he can follow doctor’s orders, he’ll be a better candidate for a heart transplant, and the pig heart will serve only as a bridge.

“The last evening I talked with the patient, he said, ‘I really want to have a human heart,’” said Dr. Bartley Griffith, who led the surgery for the University of Maryland Medicine. “I said, ‘I want you to have a human heart. … It would drive us crazy to take that nice (pig) heart out, but it would be your choice.’”

The hardest part of undertaking such experimental surgery, Griffith said, was talking to Bennett beforehand.

“You’re not afraid of demonstrating to the FDA and to the hospital and to your chairman and to your partners that you’re ready, because you’ve got confidence in that, in yourself,” he said. “I think the fear is in being honest to your patient.”

The surgery was experimental and its outcome was uncertain.

“You’ve got to tell the patient that in essence, we’re ready for liftoff,” Griffith said, adding that others compared him to a shuttle astronaut. “But I kept reminding people: we’re in the control room. It’s the patient who’s shot to the moon.”

Three experiments in one

For years, the researchers in Maryland and elsewhere have experimented with implanting gene-edited pig organs into baboons.

The University of Maryland Medicine team, co-led by Dr. Muhammad Mohiuddin, has kept baboons alive for as long as nine months, when they died of something other than immune rejection. They felt ready to try the procedure in a person.

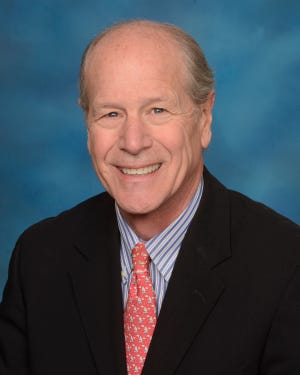

Dr. Muhammad Mohiuddin directs the program in cardiac xenotransplantation at the University of Maryland School of Medicine.

Taking care of a patient, said Mohiuddin, who directs the University of Maryland School of Medicine’s program in cardiac xenotransplantation, “it’s much, much easier than taking care of a baboon.”

Pulling off the procedure required the right patient – a willing volunteer who had no other medical options – as well as support from the hospital system and three separate approvals from the Food and Drug Administration. (The hospital and academic institution would not reveal the cost of the procedure but picked up any fees not covered by insurance.)

The process began Dec. 15, when Bennett agreed to consider the procedure. Maryland officials scrambled to provide an application to the FDA on Dec. 20, requesting “compassionate use” authorization to proceed.

Then they had to answer a slew of questions, including about the pig.

The pig, provided by Blacksburg, Virginia, company Revivicor, which raises pigs for transplant, was genetically modified in 10 different spots before birth.

“There are 100,000 genes in the pig,” Griffith said Sunday afternoon in a Zoom interview, along with Mohiuddin. “Muhammad wants me to believe that by changing 10 of them, we can transplant a pig heart into a human. Are you kidding?”

Bartley Griffith is a surgeon at the University of Maryland School of Medicine.

“You did it,” Mohiuddin responded, laughing.

Three genes were turned off that might otherwise have triggered an immediate immune rejection – the recognition of a pig organ as coming from a different species. Six human genes were added to prevent blood from coagulating in the heart, improve molecular compatibility and reduce the risk of rejection.

One final gene was turned off to keep the pig from growing too large.

The 1-year-old pig that gave its heart to Bennett weighed about 240 pounds; a standard male pig of the same age might weigh 450 pounds, said David Ayares, Revivicor’s executive vice president and chief scientific officer.

Researchers learned from studies in baboons that without editing out this growth gene, even an organ taken from a young animal would keep growing. In a couple of the baboons, the transplanted pig hearts grew too big for their chests.

“We’ve marched down this road over the last decade, going from a one-gene pig to a two- to a five- to an eight to a 10, and we rationalized each of those and made modifications along the way,” Ayares said.

Ayares has worked for two decades to develop pigs that are suitable for human transplant. Pigs bred to provide kidneys for transplant may need only one gene turned off to avoid immediate organ rejection. Pigs bred for their hearts probably need 10, Ayares said, to allow them to function effectively and safely.

Revivicor’s parent company, United Therapeutics, aims to get into pig-to-human lung transplants, whose pigs will probably need “at least that many” gene edits, Ayares said.

A second innovative aspect of the surgery is the use of an immunosuppressive medication that seems to be essential for long-term survival of a transplanted organ. Researchers had used a version developed for baboons, but this was the first time using a humanized version in a person.

A surgical team at University of Maryland School of Medicine works to give patient Dave Bennett, 57 of Maryland, a gene-edited pig heart.

The third aspect was the box that the heart was placed in after taking it from the pig. Researchers have learned that simply putting a heart on ice, as is done with a human heart, doesn’t work in between-species transplants. A German team figured out a method of perfusing the heart with nutrients and hormones.

“In the primates, the hearts just weren’t working until they started using that pump,” Montgomery of NYU said. “Nobody understands why.”

Bruno Reichart, a retired German heart transplant surgeon, who tested pig hearts in baboons for years, said he thinks the pig heart probably works better if liquid continually flows through it. But essentially, the proof is that it works.

“Who is successful is right, who is not successful is wrong. It doesn’t need much more explanation in surgery,” he said.

The FDA granted emergency authorization for the surgery on New Year’s Eve, and it was conducted Jan. 7 from around 8:30 a.m. to 5:30 p.m.

Before pig organs can routinely be used in transplant surgeries, all three aspects have to be further tested in animals to meet FDA standards. Revivicor is building a pig facility that will meet FDA production requirements.

Ayares said he and others are savoring the moment.

“This is one of the most exciting things in my 20-year-plus xeno career,” he said.

If they can provide an unlimited supply of organs, Ayares said, the organ transplant list will probably increase by “orders of magnitude,” as more people who aren’t at death’s door begin to see transplant as an option.

“We’ve done so much work up to this day,” Ayares said. “We’re confident this is going to continue to grow and build and really be the solution.”

What does success look like?

No one has been kept alive before with an organ from a specifically tailored animal. So any survival at all could be considered success.

Montgomery said he considers the surgery a success already.

“The critical thing here is we’ve moved this thing out of these endless primate operations,” he said. “We’re now going to get real data in humans and really understand this thing.”

Tector, of the University of Miami, said he wouldn’t provide a pig kidney to a patient unless he was sure the person would survive at least a year. “When we do it, we think we’re going to get reasonable survival long-term,” he said.

Reichart said he would expect Bennett could live indefinitely with his new heart.

“Maybe I’m a little obsolete and maybe from another world, but success would be at least a year,” he said. “Why shouldn’t it work for three years, for five years? We’ll see. That’s part of the experience they’ll gain now.”

Reichart, CEO of a company he co-founded to commercialize pig-to-human heart transplants, called XTransplant, said he’s concerned that Bennett was turned down for a transplant because he didn’t take previous prescriptions.

“The patient has a great responsibility to other patients in the world to behave properly and take his medications,” Reichart said. “He got the chance with the first one and everybody will look at the results.”

Griffith, the surgeon, said he’s been inspired by the efforts of so many to save Bennett and lay the groundwork for animal-to-human transplants.

“It’s been restorative to my soul to see people come together to save just one life,” he said. “They understand the implication.”